In the second installment of the Doctor’s Dozen on the Serendipitous Compendium I discuss with John the work of the German Expressionist artist, George Grosz (1893-1959).

Apart from sharing the same Christian name with Bellows who featured in the previous broadcast, Grosz was also an artist who highlighted horrors of war in his art. For Grosz, the teeming city was an apocalyptic place where human problems were concentrated into a confined space governed by individual and collective lunacy.

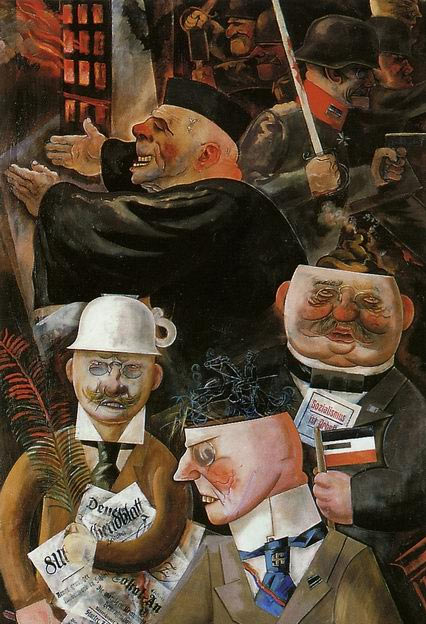

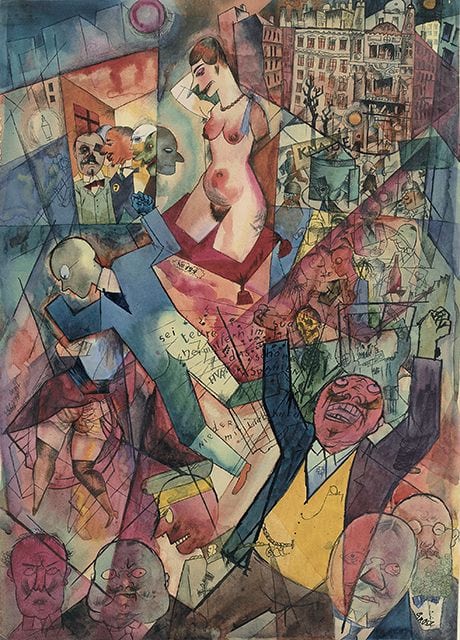

George Grosz achieved early recognition for his biting portrayals of Weimar-era Berlin, satirising the culture’s hypocrisy, military platitudes and wealthy businessmen, as in ‘Berlin Street’ (1931) from the Metropolitan’s collection [see below]. As the Met’s caption states: ‘Grosz depicts several menacing denizens of Berlin against the backdrop of the modern metropolis, a hellish place animated by greed, cruelty, and ghoulish lust. A beggar, one of the two million crippled World War I veterans who roamed the streets of Berlin, sits on the lower left and holds up his hat to a woman, whose garish attire and crude make-up suggest that she is most likely a prostitute’.

As the artist stated, “The devil knows why it should be so, but once you look more closely, people and things begin to look threadbare, ugly and often pointlessly ambiguous”. Grosz loathed what he described as “the masses” – and trusted to his own “observation, which always confirmed that the human masses are a pitiful mob, an easily influenced herd of cattle that like nothing better than to choose their own butchers”. He targeted not only “the pillars of society” – politicians, lawyers, military and ecclesiastical leaders – but the bourgeoisie in general. He saw the entire class as a decadent mire which nurtured the power of the ambitious.

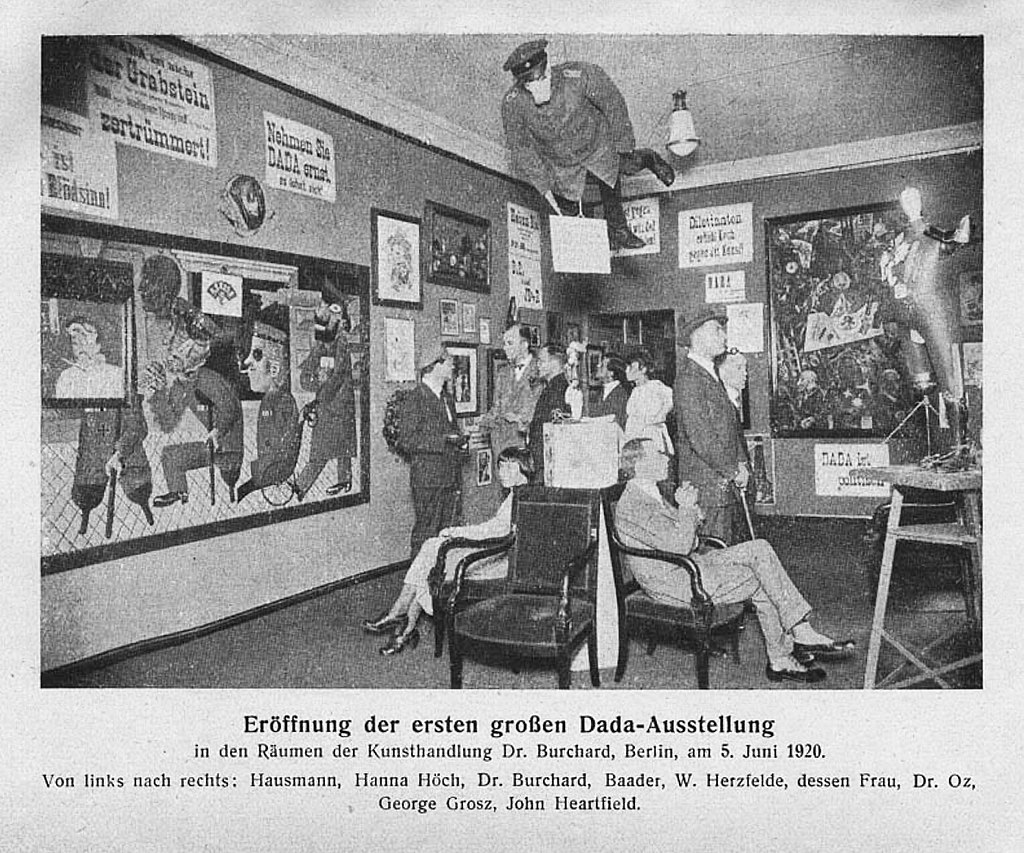

In 1917 Grosz founded the Berlin wing of the Dada movement. Dada was the artistic expression of the critique of the political and social state of affairs – the Dadaists instinctive mission was to smash the Germans’ cultural identity. Responses to the new art form, such as the Dada Show in 1920 in which Grosz participated, ranged from shock to ‘sheer nonsense’. From the ceiling of the gallery, a stuffed soldier dressed in field grey hung suspended, wearing officer’s epaulettes and with a pig mask under his cap.

Grosz’s drawings were tartly critical of society and in 1921 he was prosecuted for defamation of the army; in 1924 for offences against public morality; and in 1928 for blasphemy. Hated by the Nazis, 285 of Grosz’s works were removed from German collections – one place he was very well represented was in the 1937 show of Degenerative Art.

George Grosz left Berlin in 1932 to settle in New York, and in 1938 he was stripped of his German citizenship and became an American citizen. In the American years, the artist retreated somewhat from his former positions and his analyses took on a generalised apocalyptic tone. Becoming resigned to it, he eventually turned to landscape painting. He returned to the rubble of Berlin to live in 1959, but just 5 weeks later he was found dead after a night out drinking.

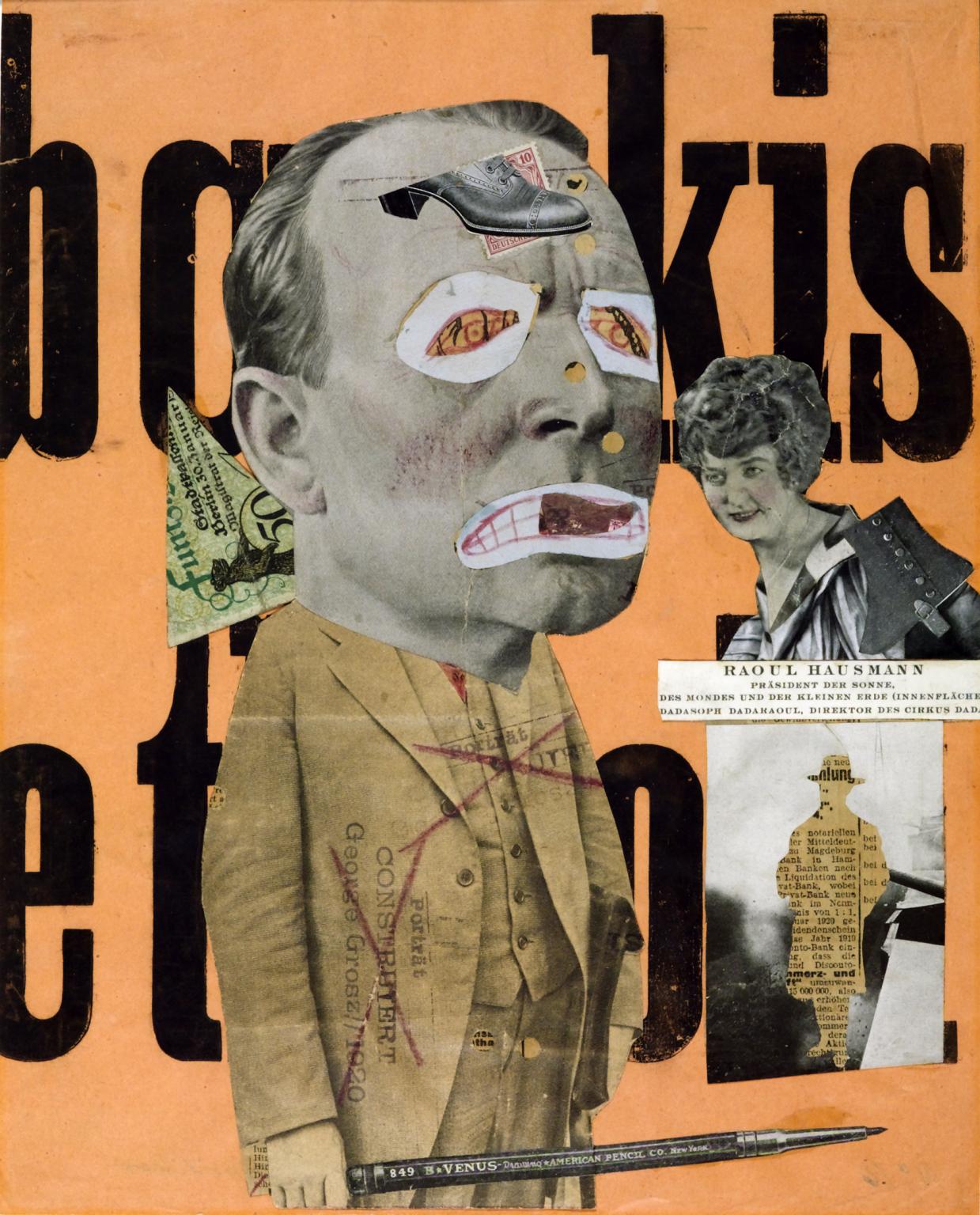

One of the best known styles associated with the Dada movement is the technique of collage or montage, which originated in Cubism and was used by a number of German artists, including the Austrian Raoul Hausmann. Connected to Grosz in this series by being, like Grosz, one of the key figures in Berlin Dada, Hausmann’s experimental photographic collages, sound poetry and institutional critiques would have a profound influence on the European Avant- Garde in the aftermath of the First World War.

His art remains fresh and astonishingly powerful today, and it is to the work of this extraordinary artist and writer that I will be discussing the third installment of the Doctor’s Dozen.