When we were discussing Pauline Boty in Part 6 of the Doctor’s Dozen on the Serendipitous Compendium, I suggested that it was high time we travelled from London back across the Atlantic to the US to find out about another artist who is considered by many scholars to be the “Godfather” and “Grandfather” of Pop art: Larry Rivers.

Rivers was one of the first artists to really merge non-objective, non-narrative art with narrative and objective abstraction.

Born in the Bronx, Larry Rivers initiated his artistic career as a jazz saxophonist in 1940 and began painting in 1945, holding his first solo exhibition in New York in 1949. To fully understand where Rivers was coming from with his art, we need to consider a precursor of the Pop Art movement and one of the leading Abstract Expressionists: Willem de Kooning.

In contrast to other Abstract Expressionists, De Kooning stayed committed to a form of figuration but also absorbed in the specifics of the urban environment and the mass media and incorporated things like newsprint into his paint surfaces, or collage from magazine images. The hard-core American Pop artists were united in their admiration for De Kooning, and he was more or less alone of his generation in having any sympathy for the younger artists. Larry Rivers met De Kooning in 1948. Mixed in with this, for Rivers, was his interest in the work of French figurative artists such as Courbet, Matisse and Bonnard.

To be deliberately provocative, he decided in 1953 to produce a painting of monumental proportions as an essay in the genre most despised at the time, the historic set-piece. He flew in the face of the whole modernist tradition and chose the most ridiculous and clichéd subject he could imagine – Washington Crossing the Delaware, something familiar to every American from the grandiose and much reproduced painting by Emanuel Leutze in the Met, NYC.

He stripped the subject of its pomp and heroism and imagined it on a more persuasively human level, concentrating on the frailty and hesitation of the figures making their way through a cold, inhospitable landscape, thus draining the loose and gestural brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists of its customary exaggerated masculine heroism.

River’s reimagining of Leutze’s painting was met with derision, but its audacity in introducing a banal subject with explicitly American connotations, encouraged many other painters by the beginning of 1960.

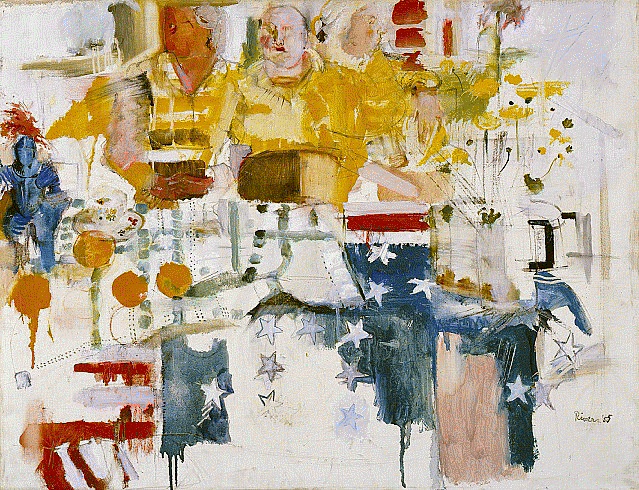

Europe I (1956) was based on old snapshots and the stars-and-stripes were introduced in fragmented form in Berdie with the American Flag (1955),

His treatment of a prototypical Pop subject in The Accident (1957) was conditioned by his taste for episodic fragments scattered across the surface like materialised memories,

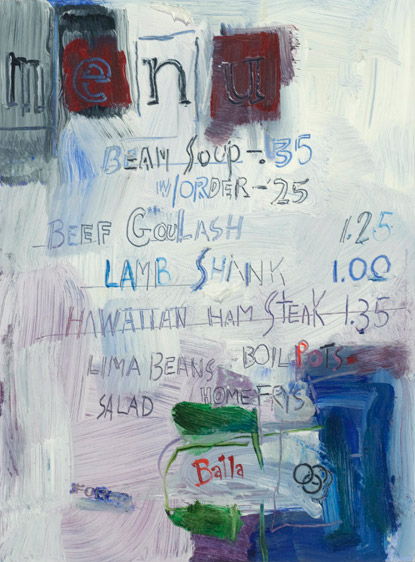

In 1959 Rivers began to paint pictures explicitly based on existing material.

Cedar Bar Menu I is a loose improvisation on the bill of fare at the Cedar Bar Tavern, then the prime meeting-place of the New York art world and particularly the Abstract Expressionist circle.

So where does all this lead us? Well, I’m going to throw a bit of a curveball now by going back to an artist I mentioned in connection with Rivers: Pierre Bonnard.

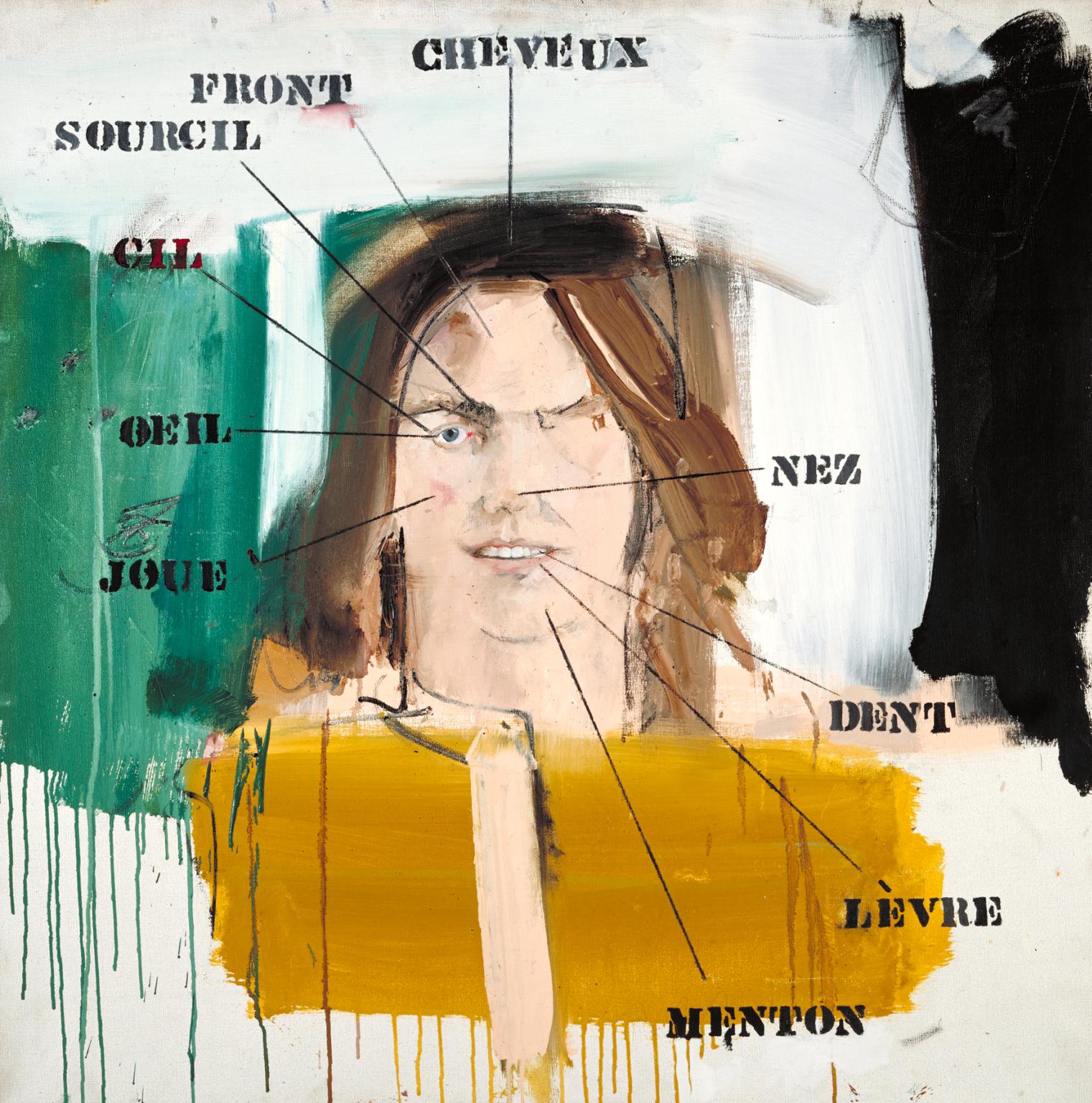

Bonnard’s work was an enormous influence on Rivers – look at this for example and compare it with ‘The Bathroom’ by Bonnard [above].

Nice insights. Good job!