As commercial galleries gradually begin to reopen in London, I booked an appointment to visit the sculpture exhibition at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill.

After donning a face mask and rubbing my hands together with a healthy blob of antibacterial hand-gloop, I was immediately attracted towards three giant sculptures. These aluminium pieces which dominate the gallery space are by the artist Urs Fischer. According to the gallery information, ‘Each sculpture began life as a small mound of clay that was squeezed instinctively in the palm of the artist’s hand. The resulting shapes were then scanned, refabricated as models over three meters high, and finally cast in aluminium, the prints of Fischer’s fingers engrained on their giant surfaces.’ It really is the fingerprints that are the thing here. These seemingly random shapes are strangely compelling when you appreciate the scale from the impressions of the artists fingers, and I found myself circling each of them several times.

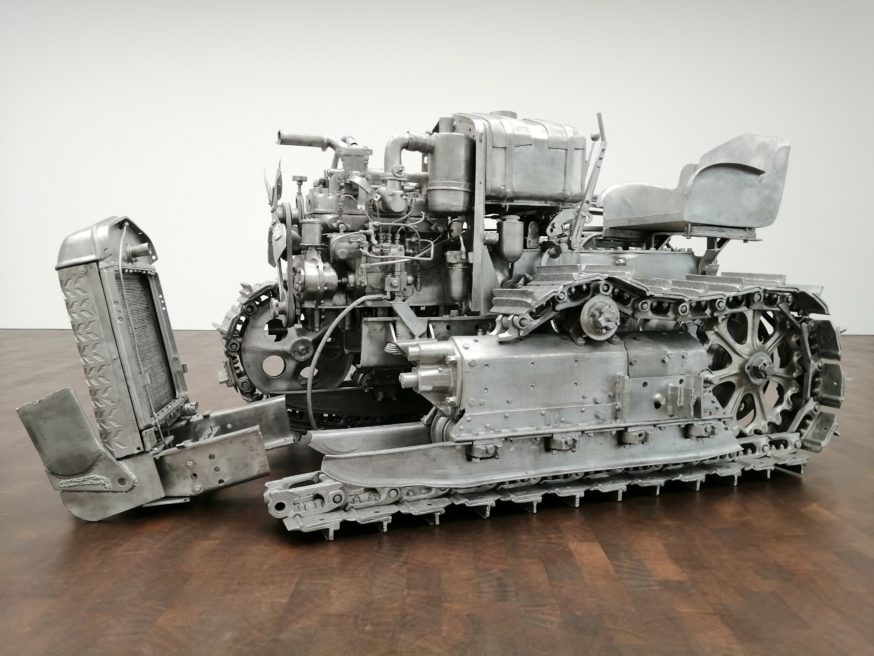

In the next gallery space is a single work by Charles Ray, but what a work it is. ‘Tractor (2003-4) is a re-creation of a rusting 1938 farming vehicle, which had become a playground for local children when the artist discovered it in a backyard in San Fernando’. What Ray then did was to remove the disintegrating tractor to his studio and dismantle it piece by piece. He made a replica of each component part by creating first a mold and then a wax version of it and casting it in aluminium before finally assembling the whole thing as a facsimile of the original, turning a rusting wreck into a beautiful, shiny object – a work of art.

For me, knowledge of (and wonder at) the painstaking process enhances my response to this. Without any mechanical knowledge on my part I still found myself staring intently at the gubbins and guts of the motor – stuff I would not usually take any interest in but here taking on new meaning and significance in terms of the relationship between the mass-produced and the handmade.

But I thought there were three artists represented here? I must have missed one – and I had. When I wandered straight to the Fischer monoliths I had not noticed the artwork on a plinth in the entrance gallery. This is by John Camberlain and his piece represents the ‘crushed’ part of the exhibition’s title.

‘Between1967 and1969, John Chamberlain produced a group of sculptures using galvanised steel […] Starting with fabricated boxes – some made and discarded by Donald Judd – Chamberlain crushed each hollow pack, compressing the sculpture into a new form’. So this is, in effect, the crushed work of another artist. It has layers, both physically and metaphorically. The material is not insignificant – galvanised steel is a manufactured metal covered in a protective layer of zinc so for Chamberlain it was ‘devoid of narrative or history’.

Lockdown has left many of us feeling a bit crushed. Perhaps we can take inspiration from these artworks and use the opportunity to recast or reconstruct ourselves.