On then to Walter Sickert, Whistler’s pupil and etching assistant. We need to keep in mind that late 19th-century Britain is characterised by the art of genteel retreat. It was French art that saw the densest flowering of artistic innovation in history – Monet, Degas, Gauguin, Cezanne, Seurat, Van Gogh, Picasso, Braque, Bonnard, Vuillard and Matisse. These were the great visual philosophers – reflecting the new conditions of a new age and embracing the difficult, differing and perplexing life of the city, new technologies and potentialities of man. But these new styles were unwelcome in Britain because they went against moral principles and met with emotional disgust.

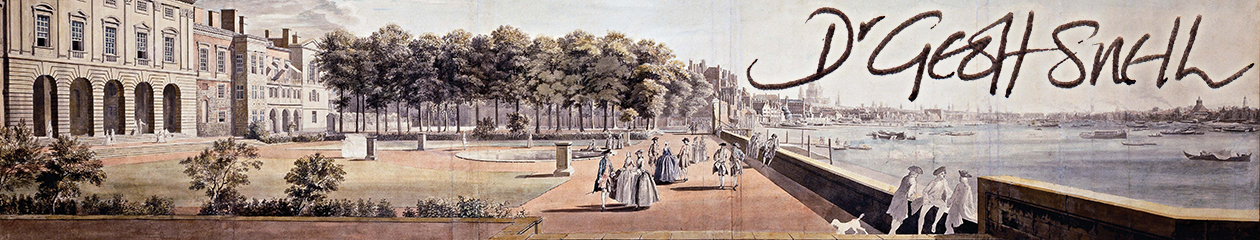

British art at this time was slick, emotionally and intellectually vacant. Even Whistler, an American in London, was producing aesthetically pleasing night time views of London and the Thames in the abstract style developed by Turner. Roger Fry’s pioneering London exhibitions of French Post-Impressionism in London in 1910 and 1912 were described by one reviewer as ‘part of a widespread plot to destroy the whole fabric of European painting’. So, into this arena enters Walter Sickert…

Sickert is one of the most imaginative British artists who captured a low-life, late Victorian world of music halls and shadowy interiors – one of the most compelling artists in the history of early modern British art. He wasn’t afraid to put sex and sleaze into his art when most British artist were timid and repressed in terms of their subjects. Sickert dared to depict the radical urban danger that artists in Paris were so alive to.

Sickert was born in Munich, Germany in 1860. In 1868 the family settled in Britain where the young Sickert first sought a career as an actor. He took up art in 1881 at Slade School – after a year he left to become a pupil and etching assistant to our friend, James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In 1883 he travelled to Paris and met Edgar Degas – and he was especially impressed by the urban realism developed by Manet and Degas. He valued the haphazard and impure texture of modern city life. He cultivated a style of painting with that glancing, snapshot quality which produced the most extraordinary art of the early modern period in British art. Sickert frequented London’s music halls, especially The Standard where George Leybourne sang Champagne Charlie and his favourite – The Old Bedford and the regular performed Minnie Cunningham. He also painted the audiences which have a ghostly quality – rapt monkeys in the dark – a flickering, gaslit human zoo.

Sickert used the popular theatre as a metaphor for existenceHe said he wanted his pictures to be like ‘pages torn from the book of life’. There’s a melancholy combined with ragged vitality.

In 1905 Sickert settled in Camden, North London – and lived among the navvies, shift-workers and prostitutes who also became his subjects. His Camden Town Nude series depicts prostitutes, liverish green in colour and sprawling on unmade beds in dark, dingy rooms. It’s another side of Edwardian life to the society portraits being produced by successful portrait artists like Whistler and Sargent.

In late 1920s and 30s he pushed painting into places it hadn’t been before by using photography and other media anticipating the art of the 1970s. His chief legacy is his realism – he gave British art back its British temperament.

Next time…

So, Sickert, influenced by Degas and Monet, introduced a sense of realism into British art. I mentioned Roger Fry’s exhibitions of French Post-Impressionism that were a desperate attempt to get London interested in the innovations going on in Paris – well somebody who was taking notice was another member of the Bloomsbury Group of which Fry was also part – Vanessa Bell.