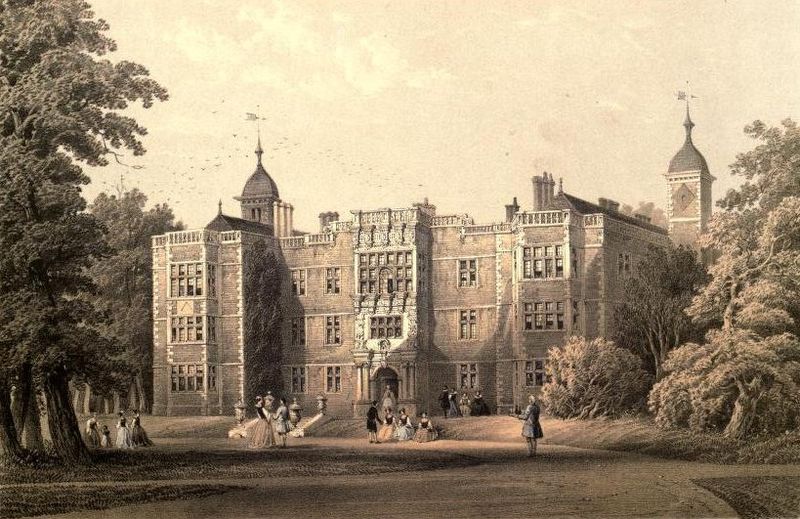

Not far from the banks of the Thames opposite my studio at Bow Creek is what is arguably the finest, best-preserved and most ambitious Jacobean mansion in London: Charlton House, and yet it attracts very little in the way of interest. The house was built between 1607 and 1612 with the then fashionable red brick with stone dressing construction and characteristic ‘E’-plan layout for Sir Adam Newton, Dean of Durham and tutor to Prince Henry, the son and heir of James I, and older brother of the future Charles I. Henry, Prince of Wales, died of typhoid fever (or was it poisoning?) at the age of 18. The diarist John Evelyn (1620-1706) lived nearby and he knew both Newton’s son, Sir Henry Newton, and the house which he recorded as being built for Prince Henry.

Evidence suggests that the architect responsible for the house was one of the

first professional English architects, Sir John Thorpe, who had served as Clerk of Works at the Palace of Placentia in nearby Greenwich. Sculptor John Wenlock Rollins’ made a statue of John Thorpe – you can find him gazing down from his niche on the external façade of the Victoria & Albert Museum above the hubbub

on Cromwell Road.

Around Charlton House itself, hidden in nooks and crannies are clues to its illustrious heritage: the Prince of Wales’ feathers above a door, the royal monogram ‘JR’ for James I somewhere else, and the royal Stuart coat of arms and the Garter and Prince of Wales’ motto , Ich Dien – ‘I serve’, in the east bay. Even more intriguing, in the grounds of Charlton House one can choose to take an architecturally interesting pee in a converted orangery which has been optimistically attributed to the greatest 17th-century architect, Inigo Jones himself. Why Jones was put in charge of designing a summer house here is unclear, but what is there for all to see is a mulberry tree, the oldest of its species, this one planted in 1608 at the behest of none other than James I himself.

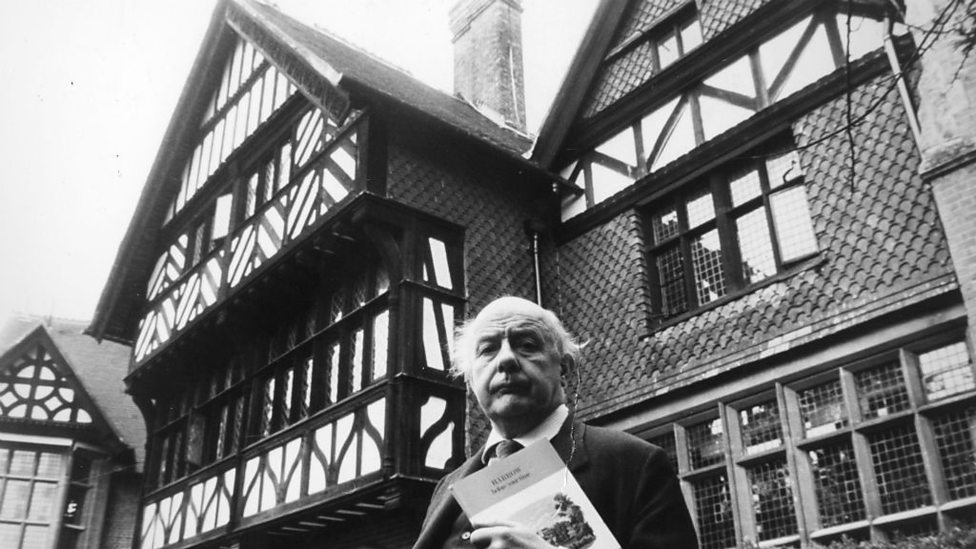

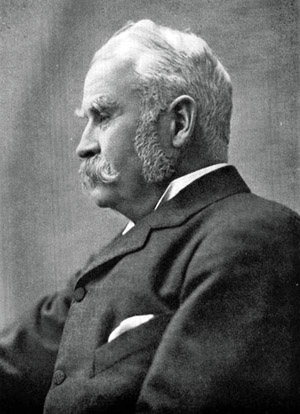

All fascinating stuff, but besides its proximity to it, what has any of this have to do with the river Thames? Well, I’ll tell you. In 1877 an extension by way of a new wing was added to Charlton House – rather controversially given its incongruous style – by the Victorian architect Richard Norman Shaw.

This architect’s legacy is huge, as he was indirectly responsible for the design of a ubiquitous variety of suburban housing in England with which many of us are only too familiar. Shaw came up with the design by drawing on ‘Queen Anne style’ and adapting it to a modern, open-plan approach, which he prototyped at place called Grim’s Dyck in Harrow, a house once visited by a bemused John Betjeman in his famous documentary Metro-land.

This house was built for the enormously successful Victorian artist Frederick Goodall, but it would later became the home of W.S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame), who died in the garden lake in an attempt to rescue a drowning girl.

Overseeing this tragic incident from an island in the lake stood a statue of Charles II by the 17th-century sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber.

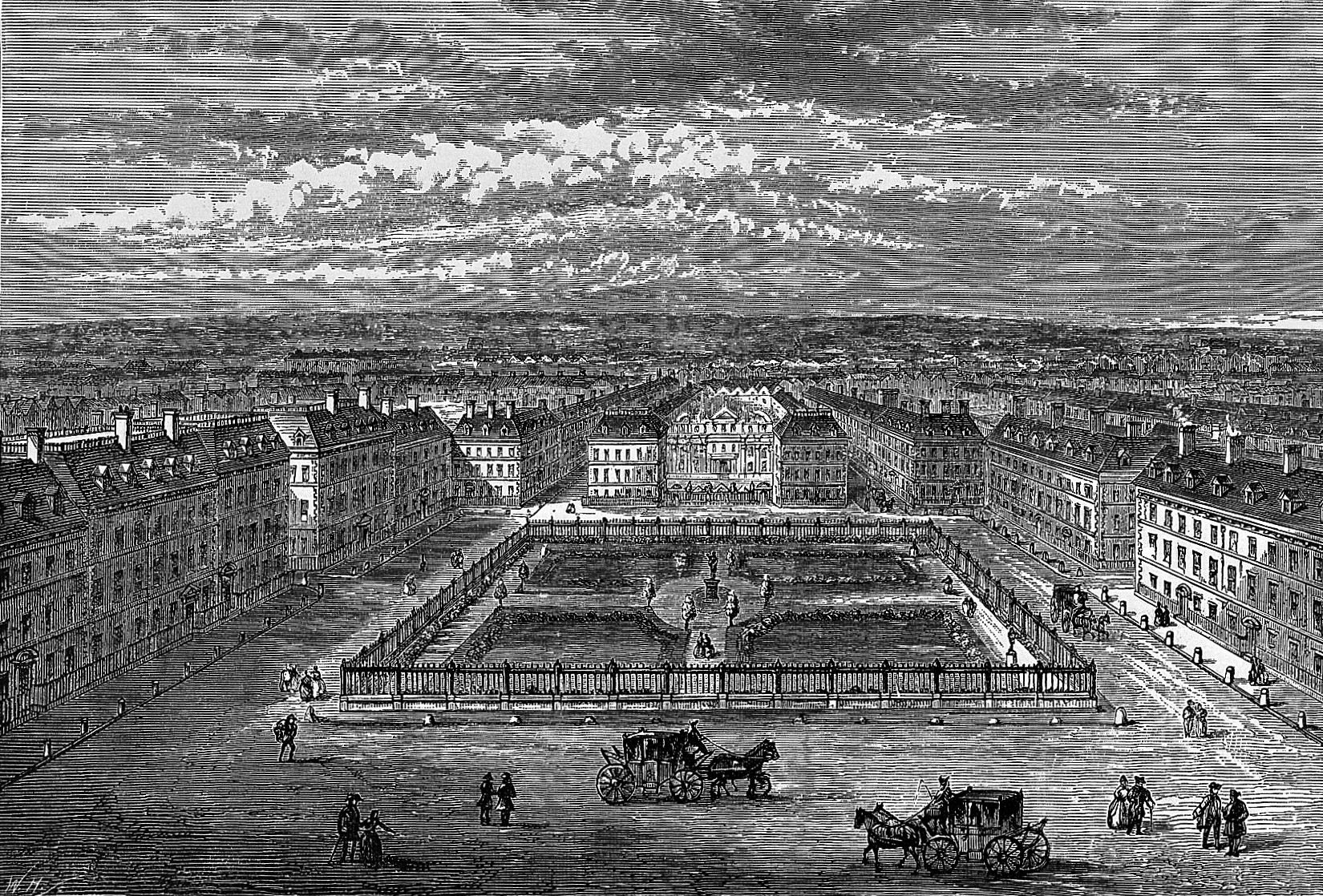

This statue of Charles II was once the centrepiece of a fountain erected in Soho Square in 1681, each corner surmounted by a statue of a river god allegorising the rivers Thames, Severn, Humber and

Tyne. Over the preceding two centuries the fountain had fallen into disrepair, but in 1875 it was removed during alterations to Soho Square by Thomas Blackwell of Crosse & Blackwell fame. The company had its headquarters at 21 Soho Square from 1838 until 1925. Crosse & Blackwell’s main warehouse in Tottenham Court Road later became the Astoria cinema and dance club, now demolished to make way for Crossrail. For safekeeping, Blackwell gave the statue (we do not know what happened to the river gods) to his friend the artist Frederick Goodall.

Incidentally, Frederick’s first commission had been for Isambard Brunel: six watercolour paintings of the Rotherhithe Tunnel. Four of these were exhibited at the Royal Academy when Frederick was sixteen. Goodall’s work received high praise and acclaim from critics and artists alike and he earned a fortune from his paintings, which is why he could afford to have a home built at Grim’s Dyke, Harrow Weald, by Richard Norman Shaw. Here he entertained guests such as the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII).

When Blackwell gave the statue of Charles II from Cibber’s fountain to Goodall, instead of restoring it, the artist had it erected on an island in his garden lake and there it remained to bear witness to the great librettist Sir William Schwenck Gilbert gasping his last in a tragic swimming accident. In 1938 Gilb

ert’s widow had the statue moved back to its original home in Soho Square, minus the river gods, where it remains today presiding over urban picnickers and the Soho glitterati.