I am in the process of collecting and collating ideas for a book that will set out to explore the impact of the River Thames on visual culture. Although I am keeping an open mind at this stage, the focus of my research is shifting towards the stretch of the river that flows between London Bridge and the sea. The business end if you like. I am interested in how visual references to the Thames – both its actual physicality and the perception of it, good and bad – have been employed as ciphers for widely held beliefs and notions that have encompassed concepts such as commerce, military power and patriotism to poverty, prostitution and suicide. Here’s something that’s caught my eye [see above]. It hails from the late nineteenth century.

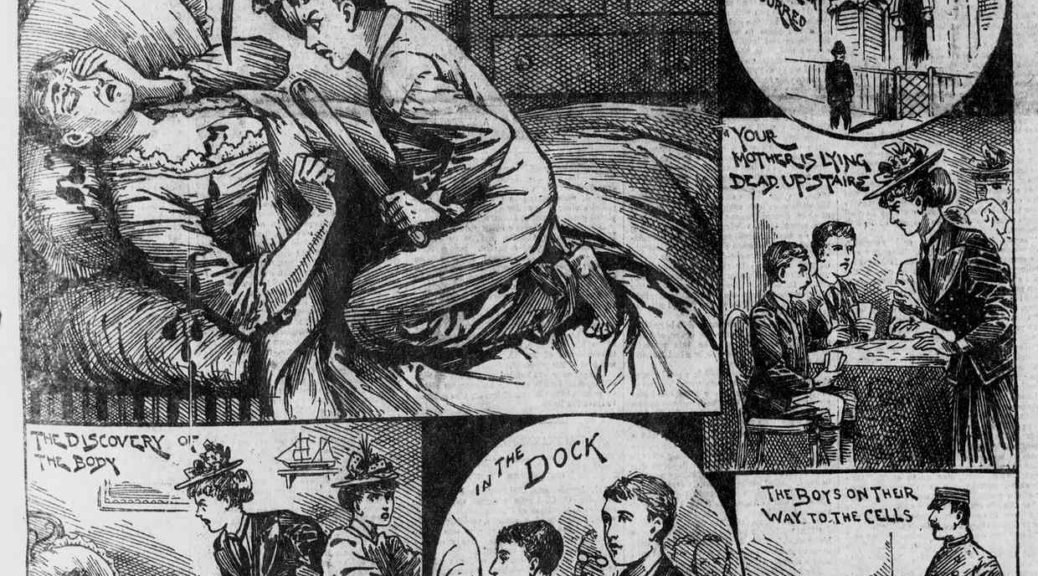

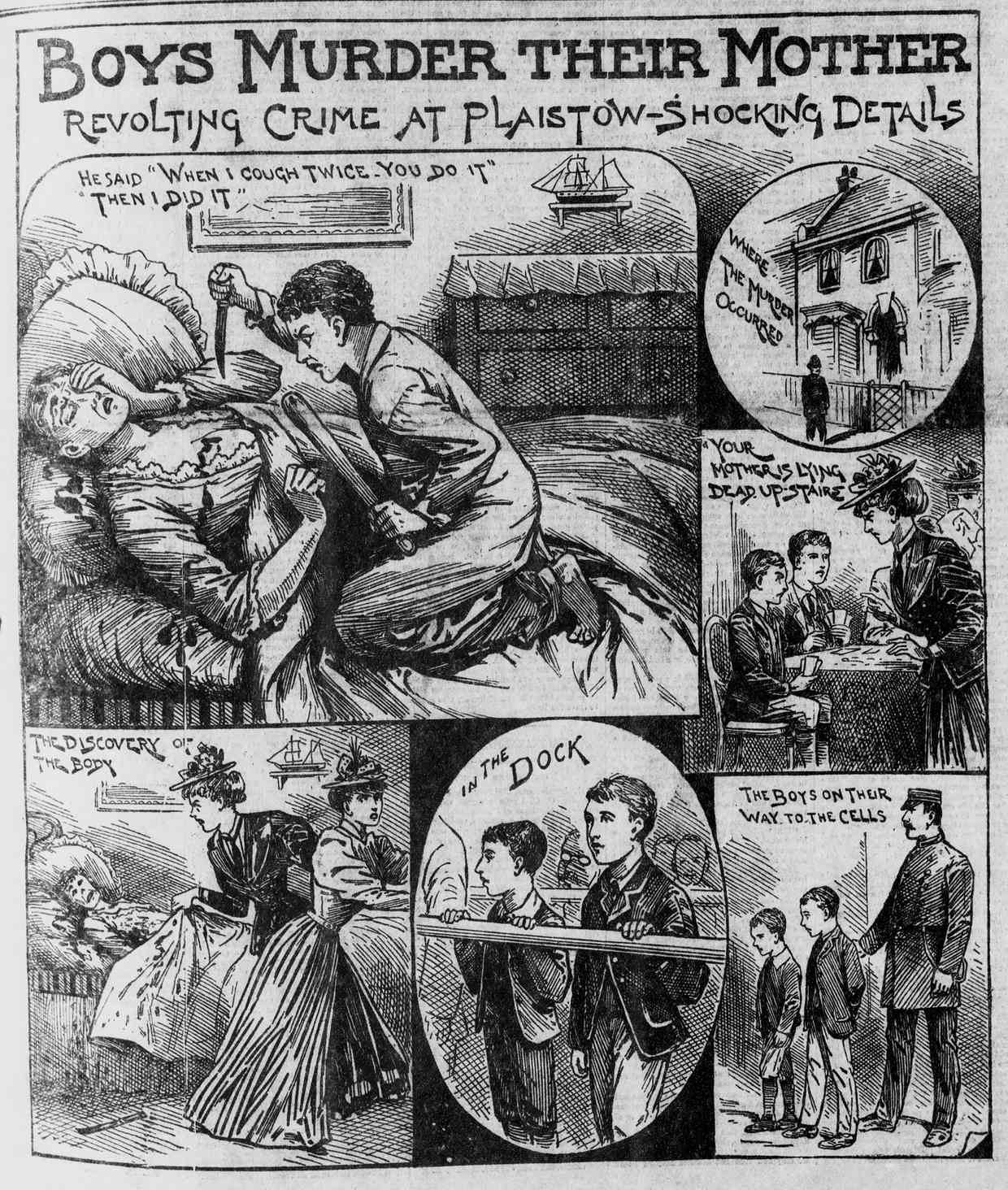

This is the cover of a typical Victorian penny dreadful and it depicts the story of a grisly murder of a mother by her two sons. It’s all a bit grim. There’s a whiff of irony about it too, for when the body was found the police had also discovered a stash of these so called penny dreadfuls, which were to all intents and purposes cheap magazines for boys. However, despite the police and coroner’s agreement that the magazines were at the bottom of the tragedy, there’s something else that might be at play here and I think the illustrator has added a visual clue that has sent me off on a different scent altogether – and this one smells of the Thames.

As Kate Summerscale makes clear in her book The Wicked Boy (Bloomsbury, 2016) it was ‘far easier to blame the penny dreadfuls than to explore the anger and fear that might have prompted a 13-year-old to attack his mother with a knife’. One cause, which emerged in court, was the eldest son’s anxiety about leaving school for a punishing job in a Thames shipyard. Given that the family lived in a small terraced house in Plaistow, east London – just a couple of miles walk from the docks and shipyards of the Thames – this explanation gains plausibility. The shipyards had a terrible reputation and working conditions and pay were dire. Could the model ship on a small shelf above the chest of drawers (which appears in both the illustrated scenes of the murder and the discovery of the body) symbolise this dreaded future employment, the fear of which might have been familiar to boys of a similar age and background at which the magazine was targeted? It may have been a shorthand reference by the illustrator but darker still, if the model ship had actually been there in the room, is it possible the mother had used its symbolic significance to taunt her sons and to threaten them with the kind of maritime future they would be doomed to suffer if they failed to do her bidding? If so, did she push it too far with her sons – aged only 12 and 13? Could they have taken her vivid threats so seriously they believed it necessary to do away with their own mother in order to avoid their perceived fate?

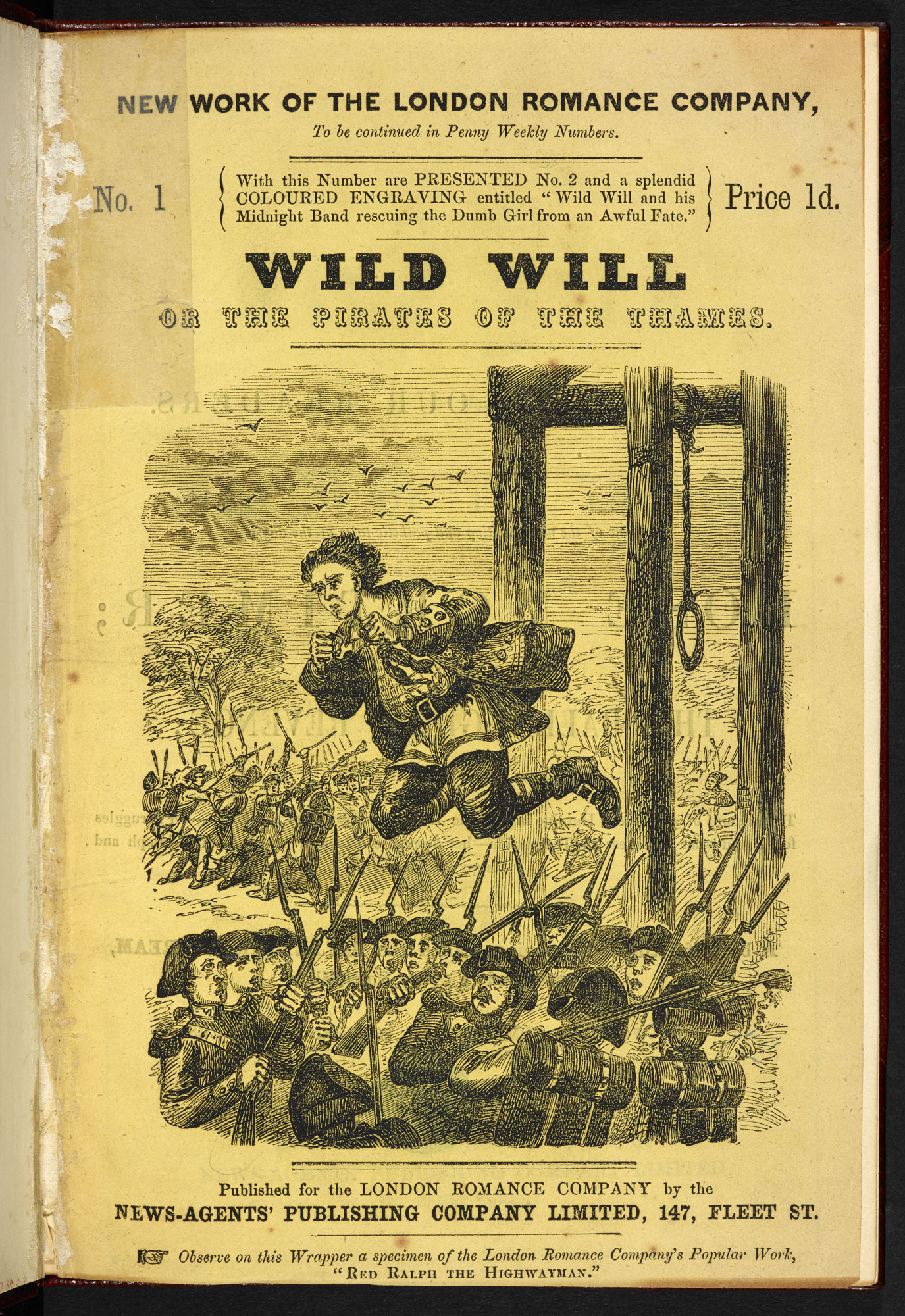

London’s river had also inspired stories for other forms of penny dreadful such as this fine tale of derring do published for the London Romance Company entitled ‘Wild Will or The Pirates of the Thames’ (c.1865). Here the maritime protagonist embarks on a series of heroic adventures with his fair maiden in tow.

It’s a million miles from the drudgery of a future condemned to toiling in a Thames shipyard, but another indication of the river’s dominant role in the real and imagined lives of young, working class Londoners in the 19th century.